The Origins of the USSR

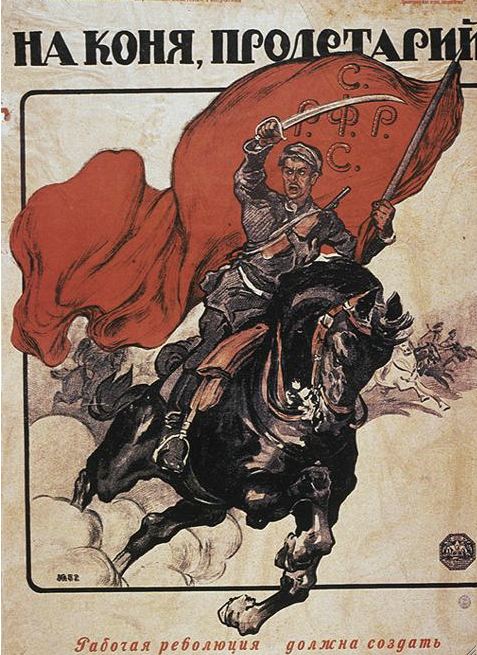

When one thinks of the USSR, the first name that comes to mind is Joseph Stalin, and even though his name is the most synonymous with them, it is important to acknowledge that his name wasn’t the first to be associated with the USSR. The origins of the USSR must be accredited to Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotsky, who followed the teachings of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Marx and Engels believed that the proletariat, working classes, would rise up against the bourgeoisie capitalist society and overthrow them by means of revolution. They were writing during a time of great political and social upheaval throughout Europe. The Revolutions of 1848 turned Europe into a powder keg of revolution that fuelled the fire underneath Marx and Engels, leading them to write ‘The Communist Manifesto’. The manifesto determined that capitalism was the enemy of society as it alienated the proletariat and constantly held them back. However, through this, capitalism had a way of destroying itself by uniting the proletariat into one unit that would rise and a communist, class-less society would emerge. The manifesto turned into somewhat of a Bible for Lenin, who developed it into Leninism which was one of the most important concepts in the beginnings of the USSR. Lenin differed from Marx in his belief that a small group of methodical revolutionaries needed to violently overthrow the capitalist system, in order for a dictatorship of the proletariat to guide society.

The beginning of the end of the Russia before communism started with the embarrassing defeat during the 1904-5 Russo-Japanese War, which was extremely costly for Russia in not only the pride department, but the human and monetary ones as well. The unrest at home with the reign of Tsar Nicholas II resulted in the 1905 Russian Revolution starting with ‘Bloody Sunday’ in St. Petersburg, where more than one hundred protesters for the Labour Movement were killed and several hundred were wounded. This horrific event was followed by a series of strikes, peasant uprisings and insurrections within the armed forces, all of which greatly threatened the Tsarist regime. The final nail in the Tsar’s monarchical coffin was the First World War. Russia was no military threat to Germany, namely because of their lack of industrialisation, and according to the 2011 report by the Robert Schuman European Centre, Russia had the greatest number of fatalities of the war, with an estimated 1.8 million deaths. This along with the rapid economic decline, soaring inflation and the political and military incompetence of Nicholas II, meant that the down-trodden Russian workers were more inclined to revolt against the present system of leadership. All of this culminated in the social unrest of the people of Russia which ultimately led to the February Revolution of 1917. The economic hardships faced by the largely dependent agrarian country, for instance Petrograd who only received half of the grain needed to feed its populace, led to the strikes of workers. It is important to note at this point that the conscription required for Russia to join the war was largely made up of the peasantry, with a third being injured by 1916. Furthermore, when Russia retreated from Poland and Lithuania in 1915, they utilised a ‘scorched earth’ policy which destroyed a monumental amount of farmland, which meant that the peasantry had no livelihood to come home to, if they came home at all. Those who did live in the cities faced massive overcrowding and unemployment if they worked in factories that did not contribute to the war effort.

On 22 February 1917, metal workers in Petrograd initiated a strike, one that would mark the end of the Tsarist regime. The following day women joined the march, protesting the present food rationing, and the numbers of strikers grew exponentially in the following days, reaching around 200,000. The overwhelming call from the protesters was for an end to Nicholas II’s reign and the end of the war. The drive of the movement meant that nearly all of Petrograd shut down, resulting in the Tsar ordering the commander of the Petrograd garrison, General Khahalov, to supress the rioting by force. Only to be surprised when the troops refused to co-operate, not only that, they mutinied and joined the protesters. The sheer lack of support from all sides forced Tsar Nicholas II to abdicate the throne, with his brother refusing to pick up the mantle. Ultimately, drawing the Tsarist regime to a close.

The Provisional Government that followed paved the way for Lenin to seize power. The eight months between Nicholas II’s abdication and Lenin taking control were inundated with political divisions and questions surrounding the legitimacy of the government itself. Firstly, those who were in charge of the Provisional Government were, for the most part, conservative with the inclination to wait for the war to end. Feelings that didn’t align with those of the Soviet who wanted the war to end, the worker to be championed and communism to thrive. Secondly, the end of the Monarchy meant that a government that reflected the will of the people could only be ascertained by an elected Constituent Assembly, which was near on impossible with a war going on. The lack of legitimacy of the Provisional Government was that it, not only, struggled to assert itself, but also found it extremely difficult to execute diplomatic decisions both at home and abroad. The struggles of the Provisional Government to declare itself the leader of Russia meant that the Petrograd Soviet had room to grow exponentially. The Petrograd Soviet had a majority of Mensheviks, who were originally the minority faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP), as opposed to Lenin’s Bolsheviks who were the majority. It is important to note that the main point of disagreement between the two factions was that the Mensheviks wanted a broad party membership for the revolution, whereas, the Bolsheviks wanted a smaller party of professional revolutionaries. Ultimately, the two factions of the RSDLP split and became their own parties in 1912.

The tide slowly shifted in 1917 in favour of the Bolsheviks, in no small way due to Lenin’s actions. This began in April after Lenin had returned to Petrograd after his exile to publish his ‘April Theses’ which at first was rejected by a gathering of Social Democrats, but was whole-heartedly accepted by the Bolshevik party after they were published in their newspaper Pravda, which was edited by Stalin. The ‘April Theses’ were a set of ten directives in which Lenin called for an end to the Provisional Government, that all power should be transferred to the Soviet, immediate withdrawal from World War I, the distribution of land amongst the peasantry, the nationalisation of banks and Soviet control of the production and distribution of goods. It was also around this time that Lenin decreed the slogan ‘Peace, Land and Bread’ which greatly resonated with the people of Russia. The consequences of these directives contributed to the ‘July Days’ uprising and ultimately the Bolshevik coup d’état that saw Lenin seize power.

The ‘July Days’ saw workers and soldiers staging armed demonstrations against the Provisional Government which resulted in the temporary decline of Bolshevik popularity. This was due to the government providing evidence that Lenin had political and financial connections with the German government. Lenin was required to flee the country, whilst others in the Bolshevik party, such as Trotsky, were arrested. The Provisional Government was reorganised with Alexander Kerensky replacing Georgy Lvov at the head seat of the table. Kerensky’s major downfall was that, despite the mass opposition to Russia’s involvement in World War I, he decided to persevere with their participation in it. This along with the ‘Kornilov affair’ which was an attempted military coup by General Lavr Kornilov who despised socialism and everything the Provisional Government stood for. Kornilov wanted to bring the old ways back through capital and corporal punishment which the Provisional Government refused to allow. Therefore, Kornilov attempted to march troops into Petrograd to arrest Bolsheviks, disperse of the Soviet and re-establish order. Kornilov claimed to have Kerensky’s approval but the history of the event dictates otherwise, and it ended with Kornilov being imprisoned and Kerensky losing all credibility in Russia.

Lenin leapt on the shaky ground of the Kerensky government and the October Revolution was established. On 25 October, Bolshevik Red Guards took control of government buildings in Petrograd, before invading the Winter Palace, and dissolving the Provisional Government. In the following days Kerensky attempted to take back control with little success and ended up fleeing to France. The irony is that during the Kornilov affair, Kerensky had armed all of the people in Petrograd, namely Soviets and Bolsheviks, which ultimately made the October Revolution possible. At the same time the Second Congress of Soviets was getting underway which saw moderates and Mensheviks condemning the Bolsheviks for their insurrection and storming out, critically giving all of the power to the Bolsheviks. The following day, after Lenin’s return from exile, he addressed the Second Congress of Soviets stating that bread would be distributed to all cities and villages, armistice ‘on all fronts’, land transfers to the peasant committees, and that all the power in the localities would pass to the ‘Soviets of Workers’, Soldiers’ and Peasants’ Deputies’. The Congress also saw the formation of a governing body that consisted entirely of Bolsheviks, Lenin was Chairman, Trotsky was Commissar for Foreign Affairs, and importantly Stalin was Commissar for Nationality Affairs.

The immediate aftermath of the October Revolution led to the Russian Civil War which was to be the last determining factor in the creation of the USSR. The main factions of the Russian Civil War were the Red Army, White Army and on a slightly smaller scale the Green Army. The Reds were made up of Lenin’s Bolsheviks, the Whites were comprised of a variety of different groups who opposed the politics of the Reds, and the Greens consisted of peasants across Russia who opposed both the Reds and Whites. One of the most important factors that meant that the Whites would ultimately lose the Civil War was that they were disorganised and didn’t have a recognised leader. The Civil War really took hold after the January Constituent Assembly, called by Lenin, that showed the opposition to his Reds after the Bolsheviks only gained a minority of the votes. However, Lenin, dissatisfied with the results, dissolved the Assembly shortly thereafter, for the state to be run solely by the Bolsheviks. After which Lenin put into place ‘War Communism’ which was a political and economic system that would further his chances of winning the Civil War. The system was one of authoritarian control that was overseen by the ruling and military castes in order to maintain power over the Soviet territories. Through it Lenin was able to control the trade sector, rail industry, food rationing and foreign trade. All of which allowed him to manipulate the narrative throughout the war in his favour. The irony being that Lenin was put into popular favour over the promise of food to the poor and through ‘War Communism’ he contributed to the Russian Famine of 1921-22. To make matters worse a number of Bolshevik revolutionaries, under the sanction of Lenin, executed Nicholas II, his wife and five children, along with their entourage on 18 July 1918.

Furthermore, in order to withdraw from World War I, Lenin signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with the Central Powers. The treaty stated that Russia lost control of Ukraine, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, and its Caucasus provinces of Kars and Batum. This comprised of 34 percent of the empire’s former population, 54 percent of its industrial land, 89 percent of its coalfields, and 26 percent of its railways. There was also a clause added that Russia had to pay Germany war reparations totalling six billion marks. The treaty was annulled after Germany surrendered to the Allied Powers later that year. However, the damage had been done between the Reds and Whites, the latter of whom believed Lenin to be a traitor. Additionally, the efforts to reclaim the lands during the Civil War had mixed results, the Reds failed in Poland and three of the Baltic countries. However, they were successful in reclaiming Azerbaijan, Armenia, Ukraine and Georgia. On top of all this Lenin and Trotsky implemented ‘Red Terror’ and created the Cheka, the Soviet secret police. They caused carnage and horror for anyone with a suspected hostility towards the Bolsheviks, by the end of the Civil War they had executed over 100,000 political opponents.

The Civil War ended in Siberia when the White Army was defeated on 25 October 1922 and resulted in the Bolsheviks consolidating power over Russia. The treaty that followed between Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan formed the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. Also known as the USSR. Lenin died on 21 January 1924, after a series of strokes. His death paved the way for Stalin to take over as the head of the USSR.

It must be questioned as to whether the birth of the USSR stayed true to the manifesto that Marx and Engels had written. A manifesto that was the original basis for Lenin’s ultimate communist empire.

The next blog post in this two-part series will focus on the rise of Stalin, the USSR’s role in World War II, the Cold War that followed, and the ultimate demise of the USSR.

Note: The dates preceding 14 February 1918, make use of the Julian calendar which was the one used throughout the Russian Revolution. It was only changed when Lenin decided to join the rest of the world, which resulted in the first thirteen days of February being lost in 1918.

About the Author

Grace E. Turton is an aspiring historical consultant with an MA in Social History and BA in History & Media from Leeds Beckett University. Grace specialises in British and Italian history but loves reading and researching about all aspects of history. In her free time, you can find her exploring the Yorkshire Dales with her dog Bear, watching classic films and playing rugby league. Grace is passionate about keeping history alive and believes that an integral part of this is maintained through History Through Fiction’s purpose.

History Through Fiction’s Newest Novel - Go On Pretending

New York Times bestselling author Alina Adams, known for her acclaimed novel My Mother’s Secret, presents Go On Pretending. This gripping tale follows three generations of women: Rose Janowitz, a 1950s TV pioneer hiding a secret romance; her daughter Emma Kagan, navigating political upheaval in the 1980s; and granddaughter Libby, joining the Women's Revolution in Syria in 2012. Adams weaves a powerful narrative of personal freedom and family bonds, enriched by her unique Soviet immigrant perspective.