Violence, Justice, and Alternative History

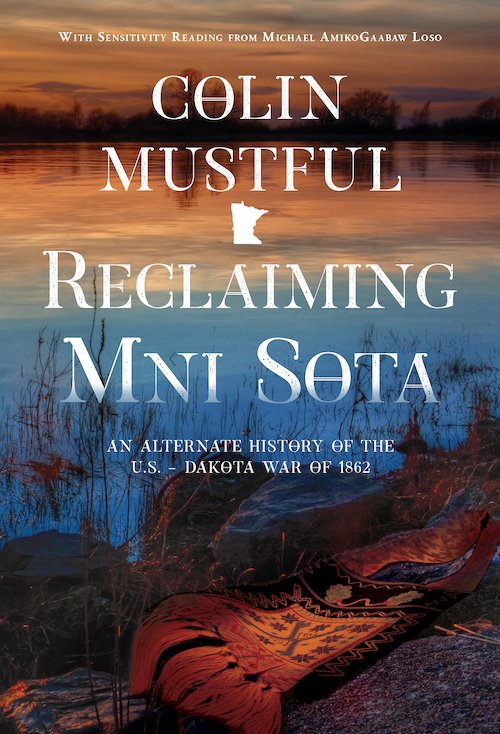

A Review of Colin Mustful’s, Reclaiming Mni Sota: An Alternate History of the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862 (History Through Fiction, 2023), 313 pp.

What if? That question permeates historical fiction. History provides threads that the novelist weaves through narrative warp and thematic weft into something new. The writer decides how much facts constrain creativity, a choice the story’s messages drive. Sometimes the author suspends the recorded past, giving imagination more freedom to explore how different history might have been.

In 1862, the United States defeated the Dakota tribe in an armed conflict in Minnesota. The defeat produced terrible consequences for the Dakota, including the internment of thousands of Indians, the largest mass execution in U.S. history, and the removal of members of the Dakota and other tribes to reservations in the west. In Reclaiming Mni Sota, Colin Mustful asks what if Native peoples had won that war.

In reimagining the conflict, Mustful turns the historical tables. The military forces of a multi-tribal alliance prevail, after which the alliance detains thousands of Americans, holds a mass execution of prisoners, and deports the American population from the land of Mni Sota Makoce. The story is radical in having Native peoples win the war. The triumph, however, involves Indian actions that replicate American behavior. Achieving a new outcome through old means creates intriguing questions about what this alternative history teaches.

Reclamation, Not Reconciliation

The plot centers on the convergence of the lives of two young men—an Ojibwe, WasabishkiMakwa—or Waabi, and an American newly settled in Minnesota, Samuel Copeland. Mustful develops their backstories to show that the reasons why Samuel’s family leaves Vermont for Minnesota are what threaten Waabi’s family, heritage, homelands, and hopes—including his affection for a young American woman, Agnes. Behind the specific events that propel Waabi and Samuel toward a fateful meeting, powerful political, economic, and cultural forces that the young men neither control nor understand are destabilizing Minnesota.

The convergence happens after the Ojibwe and Dakota tribes launch a war to end the American destruction of their peoples and ways of life. Waabi and Samuel become soldiers in the opposing armies that meet in battle at New Ulm. Samuel is wounded; and Waabi, sickened by the slaughter of war, leaves the fight only to stumble upon—and care for—the incapacitated Samuel. With difficulty, they learn to trust each other. They decide to join an armed force of Natives and Americans who oppose the war and want to prevent the conflict from producing catastrophic consequences for the inhabitants of Minnesota.

At the decisive battle at Fort Snelling, Lakota warriors arrive as part of the Indian alliance, rout the resistance force to which Waabi and Samuel belong, and contribute to the alliance’s victory over the Americans. Waabi dies at Lakota hands while saving Samuel’s life. Samuel suffers post-war internment, witnesses the mass execution of American prisoners, and is removed from Minnesota with other captives. The war destroys Waabi’s and Samuel’s desire for reconciliation between Indians and Americans.

Violence and Reclamation

In Mustful’s tale, the Ojibwe, Dakota, and Lakota alliance reclaims Native homelands, heritage, livelihoods, and dignity through superior military power. The allied armies attack and destroy American forces, forts, towns, and settlements. Allied soldiers kill those in their way, including Waabi and other Indians in the resistance force.

Those tactics recall the “total war” strategy that the Union used to defeat the Confederacy during the Civil War and, later, that the U.S. government followed in decimating Indian resistance to America’s westward expansion. In both the U.S.-Dakota war and the novel’s alternative conflict, large-scale violence—not treaties, economic relations, cultural tolerance, or recognition of a shared humanity—determines the outcome of a clash of civilizations.

That message lurks into the novel’s epilogue set in the present day. It features a case before Aazhooniingwa’on, a justice official—a Peacekeeper—of the sovereign nation of Mni Sota Makoce, where Native culture and beliefs operate alongside modern technologies, including solar energy and Tesla cars. But the scene, and the official’s title, raises questions about how peace with the United States was kept for more than 160 years. What did the Native alliance do to protect its victory from the military power that the United States developed during the Civil War and unleashed against other Native peoples across the rest of the American continent? The novel leaves such questions hanging, challenging the reader to imagine how a violent history can become a peaceful future.

Justice and Reclamation

The most jarring aspect of Mustful’s alternative history is how the Indian alliance’s post-war actions mirror what the United States did to the Dakota tribe—and Indians accused of collaborating with the Dakota—after the 1862 war. Those actions included internment of thousands of Natives in cruel conditions, hundreds of “trials” of Indians by a highly irregular military commission, the largest mass execution of prisoners in U.S. history, and the forcible removal of Native peoples from Minnesota. Those actions have long been condemned as unjust.

Why, then, does the Indian alliance engage in the same behavior? Samuel, what remains of his family, Agnes and her young son, and thousands of other American captives are imprisoned during winter with inadequate clothing, shelter, food, and water amid abysmal sanitation—conditions that produce malnutrition and disease. The alliance erects gallows and hangs 38 American prisoners for unexplained crimes, the same number the U.S. government executed in 1862. An alliance leader echoes President Abraham Lincoln’s explanation of his decision to execute only 38 Indians, rather than the hundreds the military commission sentenced to death. Finally, the alliance removes Americans from Minnesota at gunpoint.

At this point, the author imposes history on imagination rather than, as elsewhere in the novel, liberating the story from facts. Here, the tale becomes allegorical, but the meanings of the messages are enigmatic. Certainly, the mirroring highlights the injustices done by the United States by having Americans as the defeated people. How magnanimous does Lincoln’s reasoning look if Americans are the ones mistreated, put to death, and exiled under victor’s justice?

But the parallels between the U.S.-Dakota war and the novel’s alternative history also warn about a universal danger—the unchained passions, the desire for revenge, and the sense of righteousness that war spawns in belligerents. Is it far-fetched that Native peoples—endangered by relentless mistreatment—might have, following decisive military victory, engaged in inhumane treatment of captives, summary justice, and ethnic counter-cleansing?

The Spirit in the Bandolier

In the epilogue, the Peacekeeper faces a dispute over land ownership and resource use that her law clerk describes as pitting “public versus private land, American capitalism versus Native communalism.”

Curiously, the Peacekeeper carries with her the bandolier bag used by Waabi and his ancestors. Her clerk criticizes keeping a faded, tattered, and torn artifact from a traitor who opposed the alliance that created Mni Sota Makoce.

Aazhooniingwa’on responds in a way that connects the questions of violence and justice in the novel. The bandolier, she explains, belonged to someone who sought “to protect what was right and good for everyone, not just himself.” The bag holds a message for all peoples across the ages. The Peacekeeper acknowledges the past but embraces the responsibility to create a new future: “We were given this land, and we made our history. Now, finally, let us remake it.”

What if we did?

About the Author

Anthony Earth is an international lawyer and foreign policy expert who has advised governments, international organisations, and companies all over the world. He has written extensively on legal and political issues and has recently delved into outer space law and policy.

Anthony is a first-generation American, born to British parents in the Texas panhandle and raised on the plains of Kansas. He studied political science and English literature at the University of Kansas, earned graduate degrees in international relations and law from the University of Oxford, and received his J.D. from Harvard Law School.