The Jacobite Rising of 1715

In Patricia Bernstein’s novel, A Noble Cunning: The Countess and the Tower, Bethan Glentaggart travels from her estate in Scotland to London in an attempt to save her husband from execution. The novel is based on the real life story of Winifred Maxwell, a Scottish noblewoman who followed her husband, William Maxwell, 5th Earl of Nithsdale, to London after he was captured during the Battle of Preston and sentenced to death for treason. Winifred’s story is a remarkable one, and it's a story that would have never happened if not for the Jacobite Rising of 1715.

The Jacobite Rising of 1715 was a dispute over the right to the English crown—a dispute that had its origins in anti-Catholicism. This goes back to 1534, when the English Parliament passed the Act of Supremacy declaring the English crown to be "the only supreme head on earth of the Church in England.” The act was passed out of fear that the pope would impose religious and secular authority over England. It was this fear that spurred anti-Catholic persecution for centuries to follow.

Over the years, anti-Catholicism grew, especially after the Glorious Revolution of 1688 that deposed King James II, the last Catholic monarch of England. James, from the House of Stuart, was succeeded by his Protestant daughters, first Mary and then Anne. In 1714, Anne died leaving no heir.

James’ son from his second marriage, James Francis Edward Stuart, who was living in exile in France at the time, believed he was the rightful heir to the throne. James, however, was Catholic, and the Act of Settlement in 1701 strictly excluded Catholics from the throne. Therefore, Parliament overlooked James’ claim to the throne and named his German—and Protestant—cousin, George I from the House of Hanover to the throne.

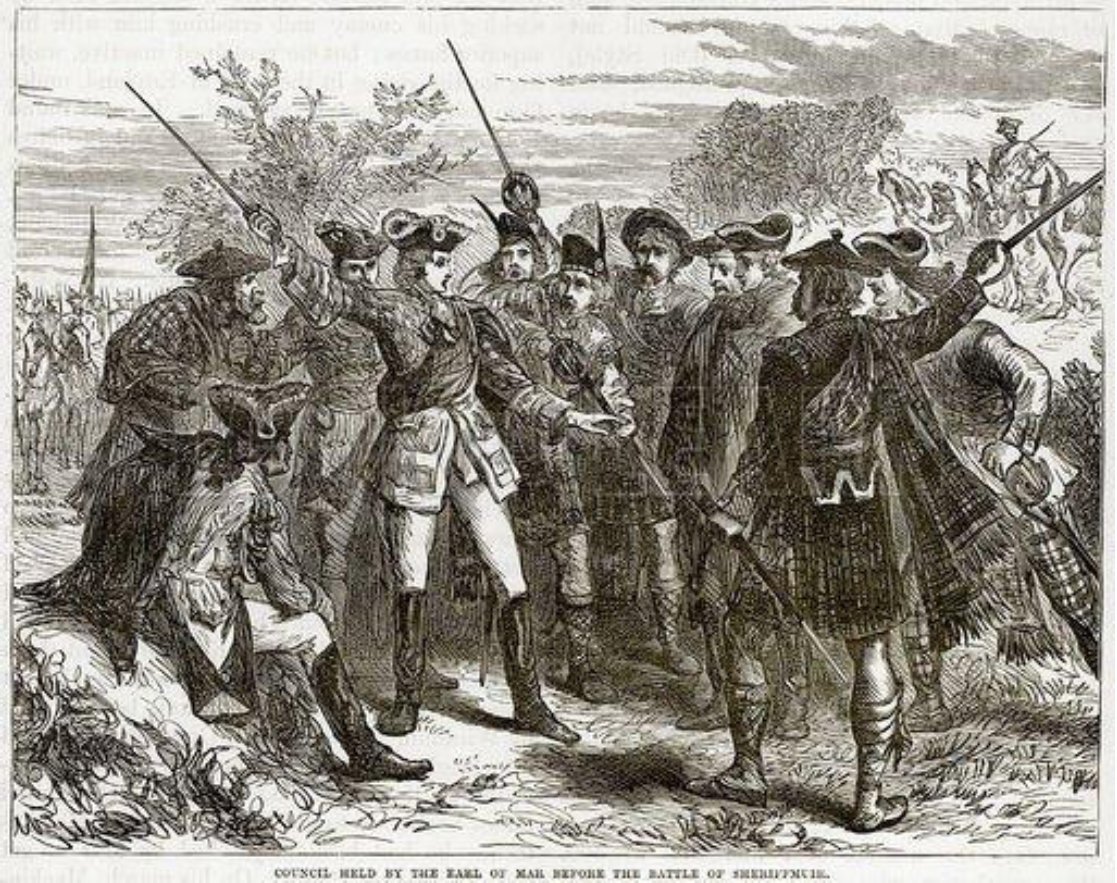

Naturally, this upset many Catholics who believed James was the rightful heir. Support for James slowly grew until, on September 6, 1715, John Erskine, the 6th Earl of Mar, raised the Stuart banner at Braemar in the Scottish Highlands. Mar began with an army of 600 men. Termed the “Jacobites,” Mar and his men enjoyed much initial success taking Inverness, Gordon Castle, Aberdeen and further south, Dundee while growing to nearly 20,000 in number. But, upon heading south into England, the Jacobites were met by hostile militias and gained few new recruits.

In November, a force of 1700 Jacobites were defeated by General Charles Wills at Preston. Among those captured was William Maxwell, 5th Earl of Nithsdale. Back in Scotland, the Jacobites continued to fight, enjoying some minor victories. But instead of advancing, Mar and his forces fell back to the Scottish highlands, perhaps waiting for James Stuart to arrive from France. Mar was pursued by John Campbell, 2nd Duke of Argyll, whose forces were growing while Mar’s forces were steadily shrinking. James Stuart finally arrived in Scotland on December 22, 1715, but it was too late to rouse his forces and the rebellion eventually petered out. In February, James and Mar left for France while men like William Maxwell in London were being tried and convicted of treason and sentenced to death. Anti-Catholic persecution would continue for many years and James Stuart never sat on the English throne.

Praise for A Noble Cunning

“I love a good historical novel about women with brains, heart, and courage. In A Noble Cunning, Patricia Bernstein’s finely-spun yarn of Jacobite sympathizer Countess of Clarencefield—inspired by the true adventures of Winifred Maxwell, Countess of Nithsdale—the author brings both the Scottish Lowlands and Hanoverian London vividly to life with a keen eye for period detail and a heart-stopping denouement.”

– Leslie Carroll, author of Notorious Royal Marriages