Religious Freedom in England - It could have happened a lot sooner than it did

This engraving by Gaspar Bouttats depicts Edward Oldcorne, a Catholic priest (foreground), and Nicholas Owen, a Jesuit lay brother (background), being tortured in the Tower of London. Edward Oldcorne; Nicholas Owen by Gaspar Bouttats, line engraving, mid 17th century NPG D17092, © National Portrait Gallery, London

The Glentaggart family in my novel A Noble Cunning suffers from anti-Catholic religious persecution, which lasted for over 200 years in Britain. But the persecution of that family and thousands of other British Catholics could have ended long before it did, if King James II had had his way. In the midst of all the bloody upheavals over religion in Europe, Britain came close to granting all of its citizens religious freedom in 1688, long before tolerance was available in other European nations.

From the time of Martin Luther’s posting of his 95 Theses on the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg in 1517, through to the reign of James II and beyond, Europe was repeatedly engulfed in extremely violent religious conflict. The effects of the Thirty Years’ War alone (1618-1648) resulted in the deaths of between four and twelve million people in Central Europe. As a result of the movement of soldiers, shifting battlefields, and displacement of farming families into crowded cities during this war, there were severe outbreaks of bubonic plague, typhus and dysentery. Food became so scarce that people tried to eat grass. There are reports that instances of cannibalism became common. And this was just one of the wars inspired by religion and the struggle for power across Europe in the name of religion.

Most of the British populace became aggressively anti-Catholic because of a series of events including:

Queen “Bloody” Mary’s efforts to force the British back into Catholicism (1553-58)

Catholic plots against Queen Elizabeth

The threat of the Spanish Armada

Guy Fawkes’ attempt to blow up Parliament and King James I on behalf of persecuted Catholics

Rumors that Catholics caused the Great Fire of London in 1666

The Spanish Inquisition

The Edict of Fontainebleau in 1685, which drove almost all Protestants (Huguenots) out of France.

Thousands of Huguenot refugees settled in England. One of them plays a key role in my novel A Noble Cunning.

The propaganda of Protestant sects which depicted the Pope as an arch-devil and the mass as an abomination.

The British not only worried about any effort to re-establish Catholicism as the official state religion but also about the invasion of England by the Catholic nations France and Spain.

From the late 1500s to the late 1700s, severe laws were in effect in England that prohibited Catholics from hosting a priest, hearing a mass, or even owning religious objects such as a rosary. Many of the homes of Catholic nobles began to feature “priest holes,” secret compartments where priests could be hidden when raiding parties invaded a house looking for an illegal priest. Catholics could not hold public office, vote, or own land, and everyone was required to attend Church of England (Anglican) services or pay a fine. The anti-Catholic laws were more stringently enforced at some times than at others but were always available when someone wanted to start a new campaign against Catholics.

King James II, a Catholic married to a very pious Catholic queen, wanted to improve conditions for fellow Catholics in England, who had been treated like traitors in their own country. When he came to the throne, he claimed the right to exempt certain Catholics from the anti-Catholic laws and appointed a number of Catholics to important positions. His actions were tolerated because he was 52 and his wife had not produced an heir, so everyone assumed his Protestant daughters would succeed him.

But in June 1688, Queen Mary of Modena had the bad taste and poor political timing to give birth to a son which, it was feared, would result in a new Catholic dynasty. James’ enemies, including his own Protestant daughters, who were now forced further from the throne in the royal succession, produced a number of rumors concerning this child. They spread gossip that James could not be the father of the baby, or that the queen had faked her pregnancy and a false princeling had been smuggled into the birthing chamber in a warming pan!

Another factor that helped to push James off his throne, ironically, was his Declaration of Indulgence, also called the Declaration for Liberty of Conscience, proclaimed by James II in 1687 and probably inspired or even actually written by the famous Quaker William Penn. The Declaration was intended to grant religious freedom to everyone, even including Jews and atheists! It would also have smoothed the way for the many burgeoning sects of Protestant dissenters who regarded the Church of England as little better than the Catholic Church. We Americans, who enjoy the benefits of religious liberty, would expect that everyone would have rejoiced at the prospect of complete freedom to follow one’s conscience in Britain, far in advance of the rest of Europe.

But many citizens did not trust James II, who, in addition to being a Catholic, was not blessed with the charm and strategic skill of Charles II, the brother who had preceded him. Those who opposed the Declaration of Indulgence thought the entire project was a plot to give more power to Catholics and eventually force the nation to return to Roman Catholicism. As for the elites, the Whig Party was aligned with the Protestants and was intent on maintaining power.

Enter William of Orange, Stadtholder of the Dutch states. William was a grandson of King Charles I married to Mary, daughter of James II and granddaughter of Charles I. At the “invitation” of a group of anti-Catholic nobles, William invaded England and deposed James II, whose forces were quickly overwhelmed in the so-called “Glorious Revolution.” Poor James, who had always feared that he might be executed as his father was in 1649, fled to France.

James’ trailblazing Declaration for Liberty of Conscience faded into historical obscurity. Catholics in England were persecuted for another 100 years and beyond. To this day, a reigning monarch in Great Britain may not be a Catholic.

About the Author

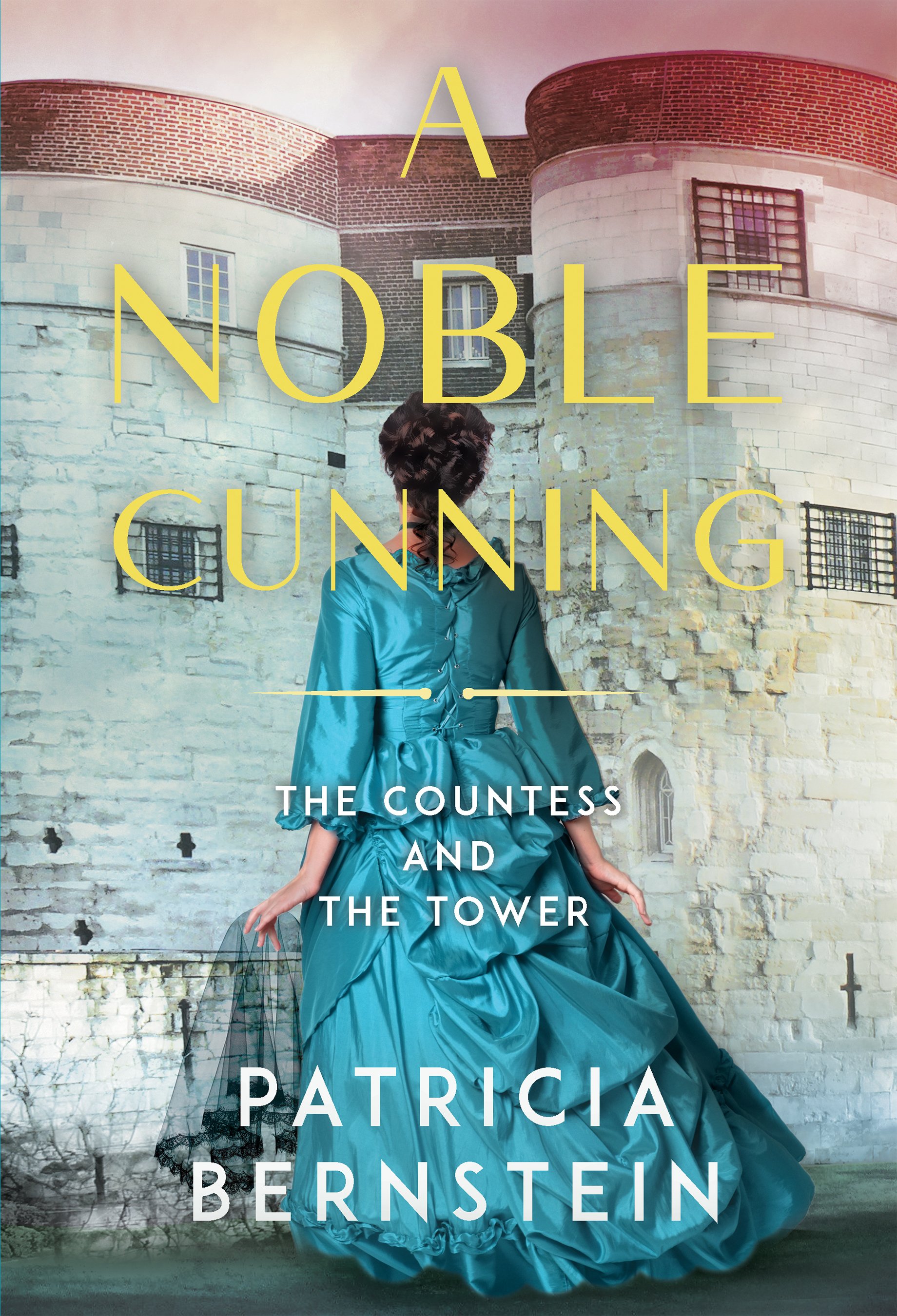

Patricia Bernstein is the author of A Noble Cunning: The Countess and the Tower, a novel based on the true story of a Catholic noblewoman who traveled to London to attempt to rescue her husband from the Tower of London the night before his scheduled execution. Bernstein is the author of three nonfiction books. She lives in Houston where she pursues her other great artistic love, singing with Opera in the Heights and other organizations. A Noble Cunning is her debut novel and it’s being published by History Through Fiction on March 7, 2023. You can learn more about Patricia and her work at PatriciaBernstein.com.