Exploring the Evolution of English through Three Famous Texts: Early Modern English

Early Modern English: Romeo and Juliet

Some find it nearly impossible to understand William Shakespeare’s plays and sonnets. Surprisingly, though, Shakespeare’s language is the closest named ancestor to today’s English, so close that it also holds in its nomenclature, “Modern English.” While the diction and syntax are certainly more archaic than what English-speakers use today, notice in this famous excerpt from Romeo and Juliet how much more similar they are than those of the Old and Middle English passages we explored in the previous posts:

JULIET: O Romeo, Romeo, wherefore art thou Romeo?

Deny thy father and refuse thy name,

Or, if thou wilt not, be but sworn my love,

And I’ll no longer be a Capulet (II.ii.36-39).

While, of course, observing the “thee,” “thou,” and “wherefore,” and the antiquated conjugations of the verb, to be (i.e., “art” and “wilt”), a modern reader is at least able to decipher the overall meaning without the need for word-for-word translation.

The Rise of Early Modern English

Early Modern English was spoken in England from around 1480 to 1685 CE. These dates are approximate as it was a gradual transition in and out of common speech, but it certainly prevailed as the dominant language in the country from the end of the 15th century to the end of the 17th century.

As mentioned in the post on Middle English, Early Modern English began to evolve as a result of the Great Vowel Shift (c. 1400 CE) when the English pronunciation of vowels moved away from the continental standard and toward a more heightened and diverse array of sounds. Additionally, around the same time, Europe began to experience an increase in literacy due to the invention the printing press in the mid-15th century. This machine enabled mass-production of pamphlets, folios, and books which, in turn, meant texts were more affordable and easily accessible to the general population.

With higher literacy rates and more efficient modes of copying text, there arose a need for standardized spelling, a foreign concept to Middle English writers and speakers. The first English dictionaries began to circulate in the mid-to-late 16th century, solidifying standard spelling and pronunciation rules, many of which remain in use today.

Why the thee, thou, you, and ye?

One of the major aspects of Early Modern English is its many variations of the pronoun, you. Modern English-speakers often assume the diverse forms of you reflect Old English patterns, but Old English is much too far back!

These additional forms of you were employed in the Medieval and Early Modern eras to denote formal versus informal modes of address. Similar to the Spanish “usted” (formal you) and “tu” (informal you), English also had grammatical norms for formal and informal second person pronouns. Although they seem fancy to us now, “thee” (objective) and “thou” (subjective) were the informal pronouns, while “you” was the formal. So, when interacting with a superior or elder, English-speakers would address them with the pronoun, “you” (e.g., “your highness”). Likewise, when addressing a subordinate or equal they would use “thee” or “thou” (e.g., “I despise thee for thou art an abomination”).

For a Shakespearean example, notice the modes of address between King Richard and his subjects in this excerpt from Richard II:

BOLINGBROKE: Your will be done: This must my comfort be:

That sun that warms you here, shall shine on me,

And those his golden beams to you here lent

Shall point on me and gild my banishment.

KING RICHARD: Norfolk, for thee remains a heavier doom,

Which I with some unwillingness pronounce:

The sly slow hours shall not determinate

The dateless limit of thy dear exile:

The hopeless word, of “never to return”

Breath I against thee, upon pain of life.

MOWBRAY: A heavy sentence, my most sovereign liege,

And all unlooked-for from your Highness’ mouth (I.iii.146-157).

Bolingbroke and Mowbray both address their king using the formal, “you/your” while the king is free to address his subjects with the informal “thee/thy” (thy is the informal equivalent to your).

Do-Support

Another interesting linguistic feature of the era is the rise in popularity of the word, do. The verb, to do, of course existed prior to this period, however the Early Modern world welcomed new modes of employing it. Between the 15th and 16th centuries, English-speakers began to incorporate this word into their vocabulary in three primary ways:

Euphuistic Do: Euphuism refers to a type of diction that was popular in Elizabethan England and most common among the elite and well-read circles. This “do” was used primarily in poetry to add rhythm, a beat where the line was lacking a beat. It was an easy metrical insert that would beautify a literary piece and keep it fitting nicely into the era’s strict metrical standards (e.g. “When I do count the clock that tells the time”, from Shakespeare’s “Sonnet 12.”).

Emphatic Do: Just as its name implies, this “do” was (and still is) used to provide greater emphasis to one’s claims, speculations, or ideas (e.g., I do believe in fairies!).

Auxiliary Do: Prior to the arrival of this “do,” English speakers would invert their sentence structures to meet the period’s grammatical rules. For example:

“Likest thou cheese within thy sandwich?”

“Nay, I like it not.”

“Then eat it not.”

Thinking about the modern English translation of the above, what word seems to be missing from each of these lines? Indeed, the missing word is “do.” With the rise of the auxiliary do, that first line, the question, began to turn into, dost thou like cheese within thy sandwich? And over time, into the modern, do you like cheese in your sandwich? The same is true for the other two lines. Incorporating this auxiliary do into the structure of questions, declaratives, and negative imperatives like these (among other grammatical forms) became the standard in English between the 18th and 19th centuries. Now, it is an absolute must!

Shakespeare’s Linguistic and Literary Legacy

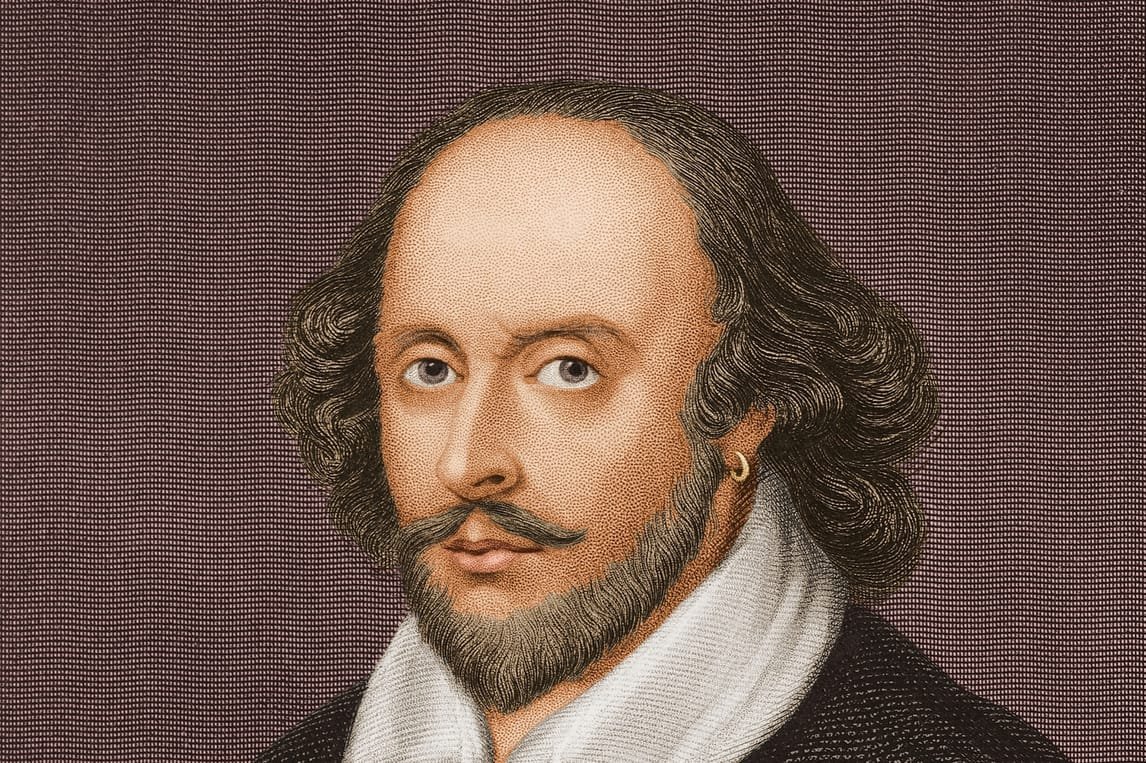

William Shakespeare (1564-1616) was a wildly influential force in his time, and he has remained so even to the present day. After his death, Ben Johnson, a contemporary and former rival wrote, “He was not of an age but for all time!” (From Ben Johnson’s “To the Memory of My Beloved the Author, Mr. William Shakespeare.”). Indeed, he is considered by many the greatest writer in the English language to date, certainly the one who has had the greatest impact on the language and its literature.

Taking advantage of everything English had to offer—its mélange of Latinate, French, and Germanic roots—especially while it was still in a malleable state, Shakespeare created at least 1,700 words and phrases, most of which are still in use today. Among these are terms like “radiance,” “love is blind,” “in a pickle,” “lonely,” “swagger,” and “good riddance.” Additionally, along with several contemporaries, he popularized the use of do-support, catalyzing its normalization and eventually standardization in the 18th and 19th centuries.

In his lifetime, he wrote at least 154 sonnets, 39 plays, and several narrative poems. Within these, he presented tragedies, comedies, histories, and romances to the world in a way that was accessible to the common person. Not only were they rich pieces of literature with profound themes and complex characterizations, but they were entertainment—people genuinely enjoyed watching his shows. And they still do today! Many of Shakespeare’s works have been adapted into modern films (e.g., The Lion King, She’s the Man, 10 Things I Hate About You, etc.), and the themes he explored in his texts continue to resonate with readers as they appear in books and other popular media worldwide. Among these is the ever-famous concept of star-crossed lovers which Shakespeare introduced and brought to life in Romeo and Juliet.

In the renowned balcony scene from where the first quoted lines of this post derive, Juliet ponders aloud, “O Romeo, Romeo, wherefore art thou Romeo?” (II.ii.36). In other words, she asks a figurative Romeo why he’s called what he’s called. It’s only because of their names—the opposing and warring families to which they belong—that they can never be together. Either he must renounce his family name or she must renounce hers. Stuck between this rock and hard place, the ardent lovers fight against fate and family to be together, and in the end, the audience is left to question which of these was the real reason for their demise—fate or the human flaws that kept their families from seeing eye-to-eye. Is this not a question that remains prevalent even today: can we control our destinies, or are some things just not meant to be?

While Shakespeare certainly didn’t invent the notion of ill-fated love, he did give the world a powerful and succinct image through which to process it, one that has become the go-to archetype for star-crossed lovers. And the same is true for the other themes and characters he presents in each of his works: the tragic hero, the complex and pitiable villain, the trickster, the fool, the monstrous, the variable lines between sane and insane, the justifications and repercussions of jealously, revenge, pride. All these and more are housed in the works of Shakespeare, the artist who generously pushed the English language and its relationship with literature into the modern structures we know and use today.

About the Author

Bex Roden is an aspiring literary artist with an interest in historical fiction. She has a formal education in English Literature centered on literary analysis and criticism, and is now expanding her focus into the realm of creative writing. She is currently an active-duty service member in the U.S. Air Force and writes in her free time.