Why a historian would dare write an alternate history

In 2007, I graduated from Minnesota State University, Mankato, with a Master of Arts degree in history. At the time, I was quite familiar with writing historical essays and presenting them at conferences such as The Northern Great Plains History Conference. One of my essays, The Tobacco Controversy of 1857, was published in the Spring 2008 Hindsight Graduate History Journal. My Master’s Thesis, The Generation of 1837: Attitudes, Policies, and Actions Toward the Indian Populations of Argentina includes hundreds of citations, an appendix displaying primary source documents, and a bibliography listing thirty-eight sources. I was, by all accounts, a burgeoning historian.

It wasn’t long before my research and writing began to focus on the U.S. - Dakota War of 1862, a tragic event that resulted in the hanging of thirty-eight Dakota people in December 1862 followed by the permanent expulsion of all Dakota people from the state of Minnesota. I found these events deeply sad and confounding. What struck me most, was the fact that, as a Minnesotan, at no point during my elementary, secondary, or post-secondary education did I learn about the U.S. - Dakota War. This is what inspired my mission, or desire, or whatever you might call it, to share the history of the U.S. - Dakota War with others.

But not as a historian.

Although I had gained a familiarity with, and integrity for, the historical process, I did not get the sense that adding another nonfiction text to the litany of other histories on the U.S. - Dakota War would have the impact I wanted—I did not believe it would reach enough readers. And so I chose fiction as my narrative vehicle because the power of storytelling is remarkable and has the ability, I believe, not only to teach readers about history but to inspire them.

This is a photo of Reconciliation Park in downtown Mankato taken during the annual Dakota 38+2 Memorial Ride & Run Commemoration. The scroll lists the names of the men who were hanged there on December 26, 1862.

As a writer, I quickly discovered that fiction presented a whole new set of challenges. First, I had to recognize and then overcome my deeply rooted historical practices. That’s not to say that my background as a historian hindered me, but it certainly influenced who I was as a storyteller and how I sought to share my message. I was stuck with the deep-seated inclination to provide every historical fact and detail as it occurred and only as it occurred. In my mind, to stretch the truth or rearrange the facts was nothing short of criminal! Needless to say, this limited my ability to tell a good story. And to my detriment, it limited my ability to reach readers with my valuable message about the history of the U.S. - Dakota War.

At the time I was unbothered by this. I believed that historical integrity was more valuable than—as the fiction writers say—emotional truths. But, after years of critical feedback from editors, and with the realization that my message simply wasn’t having the effect I wanted, I decided it was time for me to learn more about the craft of fiction. So, I returned to school for a Master of Fine Arts degree in creative writing. My degree program taught me a lot about fiction and storytelling. Mostly, it exposed me to the absolute truth that storytelling is a craft; a science; a discipline; deserving of just as much integrity as academic history

Acceptance of fiction as a craft is one thing, but how then did I find myself stretching the truth beyond fiction and all the way to alternate history? First, I had already written a novel about the U.S. - Dakota War of 1862. It’s titled Fate of the Dakota and it follows the history of the U.S. - Dakota War closely—from the outbreak of war, to the ensuing battles, to the military commission-led trials, to the final hangings. It’s fiction but it shares the facts of the history as I discovered them. If I were to write another novel about the war, I had to find a new angle. Second, a new angle, I believed, was the best way to reach the heart of my readers. Enough had been said about the U.S. - Dakota War including hundreds, perhaps thousands, of books. It was time for me to explore the emotional truths. With alternate history I was able to do that.

While there were victims on both sides of the war—white and Native—after years of researching this time period, the incredible and incessant wrongs done to Native populations stands out above all else. But, living as we do in our own minds with our own set of biases and dilemmas, it can be difficult to truly comprehend and therefore empathize with the Native situation. Or any situation outside of our own for that matter. Fiction gives us that opportunity. And alternate history, in the manner I’ve tried to express it, takes it one step further. By putting the dominant culture on the losing end and the marginalized culture on the winning end, I’m asking readers to truly imagine what it must have been like to see their homes taken away, to live as prisoners in the shadows their sacred lands, to witness the hanging of their kin, and to be exiled to a foreign territory. It’s hard to comprehend all the wrongs that have been done to the Indigenous people and cultures. I’m still trying to understand how and why it happened and what we can do to achieve justice and healing. But I hope, with my novel Reclaiming Mni Sota, readers have the opportunity to see beyond themselves and witness history not as it happened to them, but as it happened to others.

What if Minnesota was Mni Sota Makoce, a Native held and governed land?

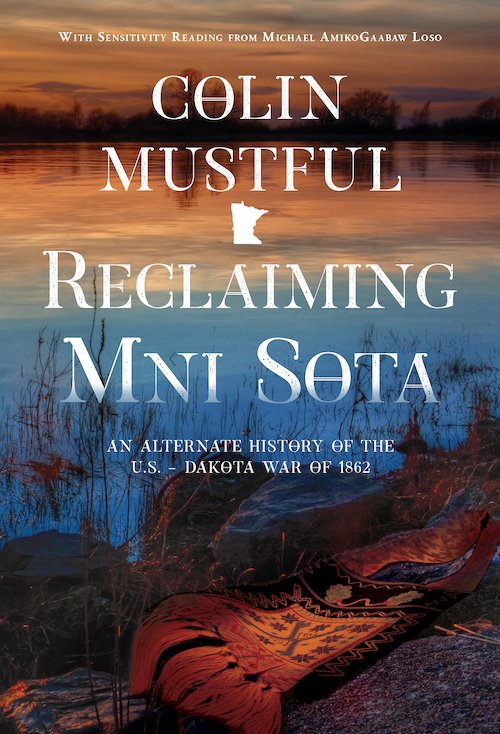

A creative re-imagining of the U.S. - Dakota War of 1862, Reclaiming Mni Sota is an eye-opening portrayal of one of America's most tragic, regrettable events. Told through dual narratives from each side of the conflict, Reclaiming Mni Sota confronts America's history of settler-colonialism while illuminating the personal stories and heartrending choices that men and women, white and Native, were forced to make. Based on real events told through descriptive detail and fully developed characters, Reclaiming Mni Sota reveals the truth of our history while connecting it to the present and asking readers to question how things could have been different.